The Paramita Center southeast

We Train the Mind through Meditation

Training the mind

The Tibetan word for meditation is pronounced “gom” (or “ghom”), and it means “to become familiar [with].”

In our culture we have many meanings for and misconceptions about “meditation.” It’s important to understand that, in our tradition, meditation starts with training the mind to focus on a chosen object. Once focused, we train to be able to rest there for as long as we intend. This is more than “watching our thoughts go by.” It is also more than mindfulness, although mindfulness is certainly part of the process of mind training.

When we train, initially, our minds are completely unruly and soon, sometimes in milliseconds, start to wander off. We start trying to concentrate, but soon we are thinking about how uncomfortable the chair is, or we start wondering what’s for dinner, or we worry about that project we must complete.

Then, the object on which we are focusing disappears from our mind. Demonstrate this for yourself: focus your attention on any object or notice your breath as it moves in and out. Try and hold your attention there, and notice how quickly your mind wanders off.

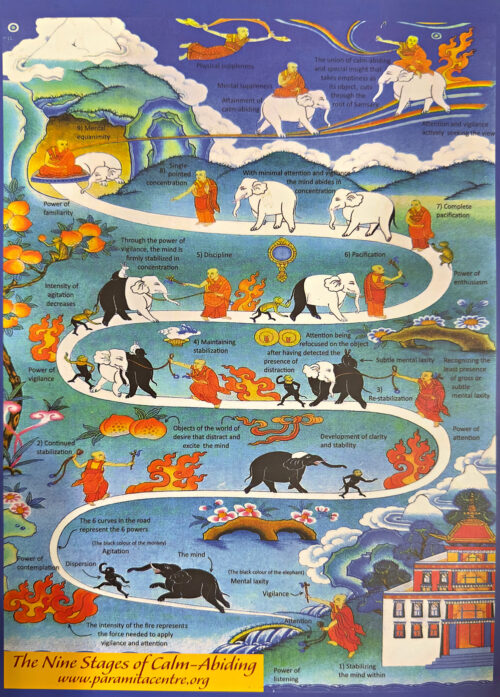

It’s like the runaway elephant and the distracted monkey in the picture.

Through training, it is possible to learn to focus for longer and longer periods. Gradually, our mind begins to stay where we place it; through focused attention we reign in the runaway elephant. We catch our thoughts wandering off earlier in the process; we begin to calm the chattering monkey through vigilance.

If this sounds like it takes effort, you’re right. Some guided “meditations” and mindfulness “exercises” are simpler, involving simply relaxing and “going with the flow.” These can feel good and can be helpful in limited ways. But learning to meditate takes a willingness to work with our minds so as to train them. It’s joyous work, but work nevertheless. In this effort, it’s helpful to have a qualified teacher who can help you get started, answer questions, and guide you through the steps of learning.

Why train in this way? For one thing, as we know from research on simple mindfulness meditation, learning to focus in this way reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, improves mood, and increases calm. These are worthy enough goals in themselves – and, to be fair, some of those more relaxing activities also have positive effects. But we also train the mind to focus so that we can become familiar with how our minds work and especially to learn how our minds can help us become happier, more contented, and more compassionate. We said above that to meditate is to “become familiar with,” and for us, the main goal is to become familiar with how to be a better person. We train in order to seek the “mental suppleness” to be able to shape our lives for the better and help others around us.

More about meditation

In learning to meditate, we take an object of meditation that we use to focus the mind. Initially, many people choose to learn to count their breath. We then learn to use an object with which we are familiar and that we can visualize. Some traditions teach to focus on an external object, such as a flower, a pleasant sound such as a singing bowl, or a candle. In our tradition, however, we train with an internal object that we learn to visualize clearly. In this way we are training the mind and not our sensory perceptions. We learn gradually to focus our mind on the internal object by visualizing it more and more clearly.

The visualized object of meditation can be a religious symbol of the faith we practice, or we can choose a simple object such as a familiar keepsake. Buddhists will typically choose the image of a Buddha to further their progress on the path, but this is not the essential point.

Initially, sessions are brief and more frequent. Sitting too long (on a meditation cushion or in a chair) at first can be discouraging and is prone to developing the bad habits of allowing ourselves to become distracted. One master has taught that in the beginning, you should always end the meditation session when you still want more – that way, when you come back to sitting, you are eager to continue, and the practice is never a drudgery.

In time, we learn to focus the mind more and more sharply and for longer periods. The important point is that the goal of this training isn’t to feel any particular way or to have a particular experience. Instead, the goal is to learn to focus and be fully present with whatever we contemplate. As we gain skill in this type of meditation, which we call concentration meditation, we can also learn to hold a thought in our mind as we contemplate its meaning. We call this analytical meditation. Both concentration meditation and analytical meditation have an important role, and we work to develop the capacity for both.

Meditating on the path to enlightenment

The skills of meditation we’ve discussed can be applied in many contexts and can be a part of any path. It is not necessary to become a Buddhist to learn meditation or to obtain benefits from the practice. For those who are interested, however, in the Buddhist path, meditation is part of our search for insight into the meaning of reality and in the service of compassion for others. More simply, we seek to become better people.

Learning in the Buddhist path is three-fold. First, we listen to teachings either from a spiritual guide or by reading. Then we contemplate what we have heard and evaluate it for ourselves. And finally, when we are convinced and understand it, we familiarize ourselves with it thoroughly in meditation. For someone who follows the Mahayana Buddhist path, ultimately the goal is to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, to become so familiarized with wisdom and compassion that we embody those qualities fully.

Can we attain enlightenment?

“Enlightenment” isn’t a place or just the ability to have special mental powers. The Tibetan word for enlightenment is pronounced Tchang Tch’up: Tchang means “purified,” and Tch’up means “replete” or “filled with.” That is, an enlightened being has thoroughly overcome obstacles to seeing reality as it is and has overcome all tendencies to harm others.

We can also think of an enlightened being as one who seeks only the benefit of others through universal compassion and the wisdom that knows how things really are. These are indeed lofty goals, and perhaps it seems impossible to attain such a state. But this is the important point: enlightenment is not the goal for its own sake or to have attained a high state for our own benefit or glory. Instead, it is to attain a state where we can, always and everywhere, work tirelessly for the benefit of others.

The great 8th-century scholar and practitioner Shatideva has taught that if even the fly will eventually become a being that can attain enlightenment, then there is no need to speak of our ability to do so!

In the end, this is why a Buddhist meditates: to learn to train the mind so that we can come to understand how to increase our own happiness and the happiness of others and to reduce our own suffering and the suffering of others.